This article and other news can be found in the latest issue of our newsletter which can be downloaded/viewed here: August 2018.

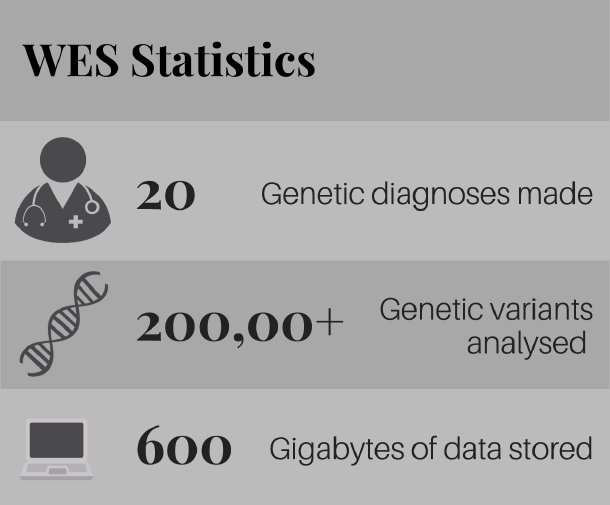

In 2014 the Hayflick lab started a project with the University of Washington to sequence DNA for our patients who did not yet have a genetic diagnosis. These 54 subjects had symptoms similar to those of NBIA but they did not have variants in any of the known NBIA genes. These samples were tested at the University of Washington using Whole Exome Sequencing (WES). The team at UW sent us back all the genetic variants they had found. These included genetic changes that were benign (not disease causing), changes that were pathogenic (disease causing), and changes with unknown effects.

Dr. Caleb Rogers started his search narrow, and looked for any variants in known NBIA genes. He then progressively broadened his scope, including genes that are associated with ataxia, dystonia and other neurological diseases. For patients who still did not have a diagnosis, he looked at genes that were known to have a strong, negative impact on the body if they are not functioning correctly. Once a potential variant is found in a gene, lab scientists like Dr. Suh Young Jeong look at the function of that gene to see if it is related to iron accumulation, CoA, autophagy, or anything else we have seen in NBIA. Dr. Hayflick and Dr. Hogarth also weigh in, and determine whether losing function in this gene would match the symptoms of the patient. If all this lines up, then a tentative diagnosis is given to the patient, and the search to find more patients with this diagnosis begins. A great example of this project in action is Mike Cohn’s road to a diagnosis of MEPAN, which you can read about here: http://nbiacure.org/decades-long-search-for-diagnosis-finally-reaches-conclusion

Even with our team searching through WES data with a fine-toothed comb, 63% of the families still have not received a diagnosis. This is the case for many reasons, such as sequencing mistakes, variants that are not in the part of the DNA that WES sequences, and the fact that we do not yet know what all of the genes in our DNA do. However, the search continues. Each time we learn about a new gene, we go through our data again, searching for another diagnosis.