If you or a loved one has recently been diagnosed with MPAN, we hope our website can help answer some of your questions and guide you to the most appropriate resources. We encourage you to call our team to speak to a genetic counselor who can help you navigate this diagnosis. Please email us at info@nbiacure.org and we will set up a phone call with you.

MPAN (mitochondrial membrane protein-associated neurodegeneration) is a NBIA disorder that is characterized by gait changes in the beginning, followed by progressive spastic paresis, dystonia, neuropsychiatric abnormalities and cognitive decline.

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of MPAN typically start to appear during childhood to early adulthood, but have been reported as late as age 30.

Common symptoms include:

Impaired gait (difficulty with walking)

- This is typically the first symptom

Muscle problems

- Early spasticity (stiff/rigid muscles)

- Sometimes followed by flaccid paresis (weak or reduced muscle tone)

Spastic paraparesis

- Exaggerated tendon reflexes

- Muscle hypertonia (high muscle tone that leads to stiffness)

- Lower limbs are affected earlier and more significantly

Babinski sign (Plantar reflex)

- When the sole of the foot is rubbed with a blunt object, the big toe flexes upwards abnormally

Dystonia (involuntarily muscle contraction and spasms)

- Often in the hands and feet

- May also be more generalized

Neuropsychiatric changes (many types have been reported)

- Emotional lability (unpredictable changes in emotions)

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Impulsivity

- Compulsions

- Hallucinations

- Perseveration

- Inattention

- Hyperactivity

Cognitive (mental) decline

- Can progress to more significant dementia in later disease

Optic atrophy (deterioration of the nerve that connects the eye to the brain)

- Usually starts during childhood

Dysarthria (speech problems)

- Difficulty using or controlling the muscles of the mouth, tongue, larynx or vocal cords which are used to make speech

- This can make a person’s speech difficult to understand in several different ways, including stuttering, slurring, or soft or raspy speech

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

Parkinsonism (symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease)

- Typically develops later in disease, during adulthood

- Bradykinesia (slow movement execution)

- Rigidity (stiffness)

- Tremors (shaking)

- Postural instability (loss of balance that causes unsteadiness)

REM sleep behavior disorder has rarely been reported

Bowel/bladder incontinence (loss of control over bowel/bladder)

- Some individuals develop incontinence early in the disease

CAUSE/GENETICS

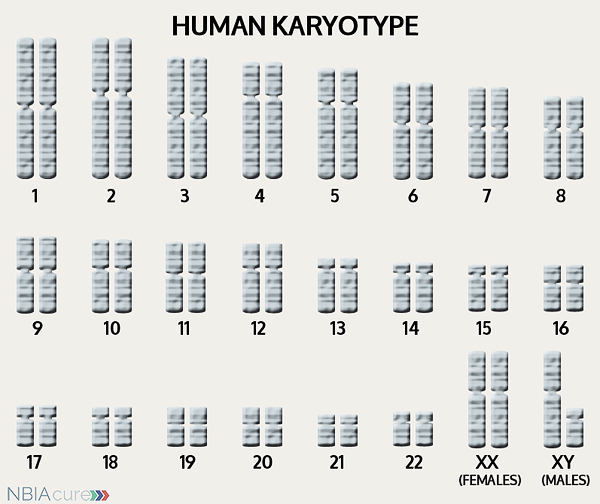

The human body is made up of millions of cells. Inside every cell there is a structure called DNA, which is like an instruction book. DNA contains detailed steps about how all the parts of the body are put together and how they work. However, DNA contains too much information to fit into a single “book”so it is packaged into multiple volumes called chromosomes. Humans typically have 46 total chromosomes that are organized in 23 pairs. There are two copies of each chromosome because we receive one set of 23 chromosomes from our biological mother and the other set of 23 from our biological father. Chromosomes 1-22 are called autosomes and the last pair is called the sex chromosomes because they determine a person’s gender. Females have two X chromosomes and males have one X and one Y.

The human body is made up of millions of cells. Inside every cell there is a structure called DNA, which is like an instruction book. DNA contains detailed steps about how all the parts of the body are put together and how they work. However, DNA contains too much information to fit into a single “book”so it is packaged into multiple volumes called chromosomes. Humans typically have 46 total chromosomes that are organized in 23 pairs. There are two copies of each chromosome because we receive one set of 23 chromosomes from our biological mother and the other set of 23 from our biological father. Chromosomes 1-22 are called autosomes and the last pair is called the sex chromosomes because they determine a person’s gender. Females have two X chromosomes and males have one X and one Y.

If DNA is the body’s instruction book and it is stored in multiple volumes (called chromosomes), then genes would be the individual chapters of those books. Genes are small pieces of DNA that regulate certain parts or functions of the body. Sometimes multiple genes (or chapters) are needed to control one function. Other times, just one gene (or chapter) can influence multiple functions. Since there are two copies of each chromosome, there are also two copies of each gene. In some gene pairs, both copies need to be expressed (or turned on) in order for them to do their job correctly. For other genes pairs, only one copy needs to be expressed.

When a single cell in the human body divides and replicates, its DNA is also replicated. This replication process is usually very accurate but sometimes the body can make a mistake and create a “typo” (or mutation). Just like a typo in a book, a mutation in the DNA can be unnoticeable, harmless, or serious. A mutation with serious consequences can result in a part of the body not developing correctly or a particular function not working properly.

In the case of NBIA disorders, changes in certain genes cause a person to develop their particular type of NBIA. Changes in these NBIA genes lead to the groups of symptoms we observe, although we do not yet understand how the changed genes cause many of these findings. C19orf12 is the only gene known to cause MPAN. C19orf12’s main job is to tell the body’s cells how to make a protein whose function is unclear, although we know the protein works in the mitocondria. It is also not clear how a decrease in this protein eventually leads to iron accumulation in the brain.

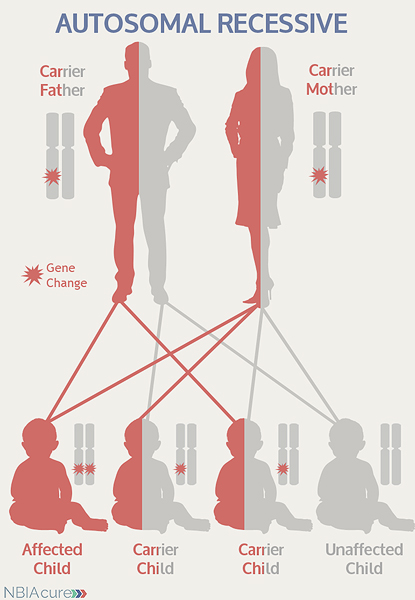

As mentioned earlier, humans have a total of 23 pairs of chromosomes. Half of these chromosomes are passed down (or inherited) from the biological mother and half from the biological father. The way in which a gene change is passed down from parents to child varies from gene to gene. The C19orf12 gene that is altered in those with MPAN is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.

“Autosomal” refers to the fact that the C19orf12 gene is located on chromosome 19, which is one of the autosomes (chromosome pairs 1-22). Since the sex chromosomes are not involved, males and females are equally likely to inherit the changed gene. “Recessive” refers to the fact that a gene change must be present in both copies of the C19orf12 gene for a person to have MPAN. If an individual has only one C19orf12 gene change, then they are called a “carrier” for MPAN. Carriers do not have health problems related to that gene change and often do not know they carry a recessive gene change. However, if two MPAN carriers have a child together, then there is a 25% chance that they will both pass on their recessive C19orf12 gene changes and have a child with MPAN.

As seen in the image to the left, in a pregnancy between two MPAN carriers:

As seen in the image to the left, in a pregnancy between two MPAN carriers:

- There is a 25% chance of the child having MPAN

- There is a 50% chance that the child will be a carrier like his/her parents

- There is a 25% chance that the child will not have MPAN or be a carrier

DIAGNOSIS & TESTING

A brain MRI is a standard diagnostic tool for all NBIA disorders. MRI stands for magnetic resonance imaging. An MRI produces a picture of the body that is created using a magnetic field and a computer. The technology used in an MRI is different from that of an x-ray. An MRI is painless and is even considered safe to do during pregnancy. Sometimes an MRI is done of the whole body, but more often, a doctor will order an MRI of one particular part of the body.

Evidence of iron accumulation on a brain MRI is often an important clue leading to the diagnosis of MPAN. A T2 sequence is the preferred type of MRI for MPAN diagnosis because it is highly sensitive to the detection of brain iron.

MRI findings for MPAN include:

- Hypointensity (darkness) in the globus pallidus and substantia nigra on T2 MRI

- Dark patches indicate iron accumulation

- Does not have the “eye-of-the-tiger” sign seen in PKAN

- Some individuals have hyperintense (bright) streaking in the globus pallidus that might be mistaken for an “eye-of-the-tiger sign”

- Less common MRI abnormalities include:

- Generalized cortical atrophy

- Cerebellar atrophy (degeneration of the cerebellum)

- Hyperintensity (brightness) in the caudate nucleus and putamen on T1 MRI

Diagnosis of MPAN is confirmed through genetic testing of the C19orf12 gene to find two gene changes. At least one C19orf12 gene change is found through DNA sequence analysis in ~95% of individuals.

Sometimes an individual with the signs and symptoms of MPAN will have only one or even no C19orf12 gene changes identified. This can happen because the genetic testing is not perfect and has certain limitations. It does not mean the person does not have MPAN; it may just mean we do not yet have the technology to find the hidden gene change. In these cases it becomes very important to have doctors experienced with MPAN review the MRI and the person’s symptoms very carefully to be as sure as possible of the diagnosis.

MANAGEMENT

There is no standard treatment for MPAN. Patients are managed by a team of medical professionals that recommends treatments based on current symptoms.

There is no standard treatment for MPAN. Patients are managed by a team of medical professionals that recommends treatments based on current symptoms.

After diagnosis, individuals with MPAN are recommended to get the following evaluations to determine the extent of their disease:

- Neurologic examination for dystonia, spasticity, parkinsonism and neuropsychiatric changes

- Evaluation of ambulation and speech

- Developmental assessment

- Assessment for physical therapy, occupational therapy, and/or speech therapy

- Medical genetics consultation

Dystonia (involuntarily muscle contraction and spasms) can be debilitating and distressing to affected individuals and their caregivers. The therapies for managing dystonia vary in method and success rate.

Therapies to manage dystonia can include:

- Intramuscular botulinum toxin

- Botox is injected in spastic, dystonic muscles to help them relax for a period of time

- Artane (trihexyphenidyl), taken orally, usually divided into multiple doses each day

- Baclofen (oral or intrathecal)

- One of the main drugs used to treat dystonia, usually first taken orally and divided into several doses each day

- In the intrathecal method, an implanted baclofen pump delivers medication directly into the spinal fluid

- Deep brain stimulation

- Used increasingly more often in NBIA and has some evidence for benefit

- A stimulator sends electrical impulses to the affected brain region to help muscles relax

- It involves surgical implantation of a lead, extension and battery pack (IPG)

- The lead contains 4 electrodes and is implanted in the globus pallidus region of the brain

- The extension connects the lead to the battery pack (IPG)

- The IPG is a battery-powered neurostimulator that is placed in the abdomen (or in some cases below the clavicle)

- Physical and occupational therapy

- May or may not be indicated for those who are only mildly symptomatic

Medication to manage parkinsonism:

The symptoms of parkinsonism and dystonia can be treated with the same medications used in Parkinson’s disease. Treatment with dopamine agonist drugs (like levodopa) must be started and monitored carefully. In the beginning, the dose is increased gradually until both the patient and doctor feel symptoms are under control. While taking dopaminergic drugs, individuals must be regularly monitored for adverse neuropsychiatric effects, psychiatric symptoms and worsening of parkinsonism.

It is common for individuals to have an initially dramatic positive response to the dopamine agonist drugs, but this response tends to be short-lived and is quickly followed by the development of motor fluctuations and dyskinesias (unwanted movement). Despite these side effects, treatment with dopamine agonist drugs is often continued because affected individuals typically experience benefits from the medication for some time while the dyskinesias are expected to decline after medication is discontinued.

Even after a diagnosis has been made and the appropriate therapies have been decided, it is recommended to continue long-term surveillance to decrease the impact of MPAN symptoms and increase quality of life.

Long-term surveillance for MPAN can include:

- Monitoring of individuals receiving dopaminergic drugs for parkinsonism for:

- Adverse neuropsychiatric effects

- Psychiatric symptoms

- Worsening of parkinsonism

- Treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms by a psychiatrist

- Physical, occupational, speech, and other therapies (as indicated)

- Feeding modifications to prevent aspiration pneumonia and achieve adequate nutrition

- Addition of gastric feeding tube or tracheostomy (if needed)

- Routine eye exams

PROGRESSION

The progression of MPAN is usually slow, with survival well into adulthood. However, rare individuals with abrupt adult onset and rapid progression have been reported. Individuals with MPAN learn to walk and are usually mobile into early adulthood.

The end stages of MPAN are characterized by progressive dementia, spasticity, dystonia, and parkinsonism. Limited speech, weight loss and bowel and/or bladder incontinence are also common. The average lifespan varies for individuals with MPAN, but due to improvements in medical care, more affected individuals are now living well into adulthood. Secondary complications, like aspiration pneumonia or other infections, are the most frequent cause of death.

Copyright © 2014 by NBIAcure.org. All rights reserved.