Neuroferritinopathy is a NBIA disorder characterized by symptoms that are similar to Huntington disease with adult-onset chorea or dystonia and cognitive (mental) changes.

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of neuroferritinopathy typically start to appear around age 40, but can range from the early teenage years to age 60

Common symptoms include:

Chorea (brief, repetitive, jerky, uncontrolled movements)

Dystonia (involuntarily muscle contraction and spasms)

- Affects one or two limbs in the beginning and progresses to other limbs within 5-10 years

- Onset is often asymmetrical (occurs differently in bilateral limbs or muscles)

- If asymmetry occurs, it will remain throughout the course of the disease

Parkinsonism (symptoms similar to Parkinson’s disease)

- Bradykinesia (slow movements)

- Increased tendon reflexes

Speech problems

- Dysarthria

- Difficulty using or controlling the muscles of the mouth, tongue, larynx or vocal cords, which are used to make speech

- This can make a person’s speech difficult to understand in several different ways, including stuttering, slurring, or soft or raspy speech

- Results in a jerky, quivery, hoarse, tight, or groaning voice

Dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

Eye problems

- Abnormal EOM (extraocular movement)

- Movement of the eye in one or more directions is abnormal

Subtle cognitive (mental) decline

CAUSE/GENETICS

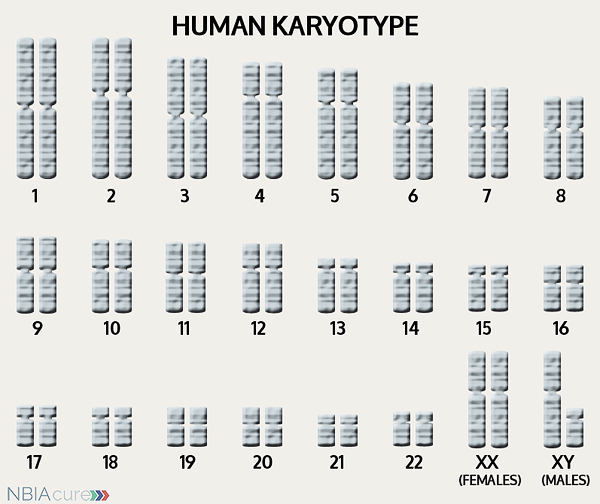

The human body is made up of millions of cells. Inside every cell there is a structure called DNA, which is like an instruction book. DNA contains detailed steps about how all the parts of the body are put together and how they work. However, DNA contains too much information to fit into a single “book,” so it is packaged into multiple volumes called chromosomes. Humans typically have 46 total chromosomes that are organized in 23 pairs. There are two copies of each chromosome because we receive one set of 23 chromosomes from our biological mother and the other set of 23 from our biological father. Chromosomes 1-22 are called autosomes and the last pair is called the sex chromosomes because they determine a person’s gender. Females have two X chromosomes and males have one X and one Y.

The human body is made up of millions of cells. Inside every cell there is a structure called DNA, which is like an instruction book. DNA contains detailed steps about how all the parts of the body are put together and how they work. However, DNA contains too much information to fit into a single “book,” so it is packaged into multiple volumes called chromosomes. Humans typically have 46 total chromosomes that are organized in 23 pairs. There are two copies of each chromosome because we receive one set of 23 chromosomes from our biological mother and the other set of 23 from our biological father. Chromosomes 1-22 are called autosomes and the last pair is called the sex chromosomes because they determine a person’s gender. Females have two X chromosomes and males have one X and one Y.

If DNA is the body’s instruction book and it is stored in multiple volumes (called chromosomes), then genes would be the individual chapters of those books. Genes are small pieces of DNA that regulate certain parts or functions of the body. Sometimes multiple genes (or chapters) are needed to control one function. Other times, just one gene (or chapter) can influence multiple functions. Since there are two copies of each chromosome, there are also two copies of each gene. In some gene pairs, both copies need to be expressed (or turned on) in order for them to do their job correctly. For other genes pairs, only one copy needs to be expressed.

When a single cell in the human body divides and replicates, its DNA is also replicated. This replication process is usually very accurate but sometimes the body can make a mistake and create a “typo” (or mutation). Just like a typo in a book, a mutation in the DNA can be unnoticeable, harmless, or serious. A mutation with serious consequences can result in a part of the body not developing correctly or a particular function not working properly.

In the case of NBIA disorders, changes in certain genes cause a person to develop their particular type of NBIA. Changes in these NBIA genes lead to the groups of symptoms we observe, although we do not yet understand how the changed genes cause many of these findings. FTL is the only gene known to cause neuroferritinopathy. FTL’s main job is to tell the body’s cells how to make the light subunit of the ferritin protein, which is responsible for iron uptake and release.

As mentioned earlier, humans have a total of 23 pairs of chromosomes. Half of these chromosomes are passed down (or inherited) from the biological mother and half from the biological father. The way in which a gene change is passed down from parents to child varies from gene to gene. The FTL gene that is altered in those with neuroferritinopathy is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.

“Autosomal” refers to the fact that the FTL gene is located on chromosome 19, which is one of the autosomes (chromosome pairs 1-22). Since the sex chromosomes are not involved, that means that males and females are equally likely to inherit the altered gene. “Dominant” refers to the fact that having a gene change in just one of the two gene copies is all it takes for a person to express a trait.

As seen in the image to the left, when one parent has a dominant gene change, there is a 50% chance that any child they have will inherit that change. Since the gene change is located on an autosome, the gender of the child (whether it is a son or daughter) does not affect this pattern. Girls and boys will be affected equally. Most individuals diagnosed with neuroferritinopathy have an affected parent.

DIAGNOSIS & TESTING

A brain MRI is a standard diagnostic tool for all NBIA disorders. MRI stands for magnetic resonance imaging. An MRI produces a picture of the body that is created using a magnetic field and a computer. The technology used in an MRI is different from that of an x-ray. An MRI is painless and is even considered safe to do during pregnancy. Sometimes an MRI is done of the whole body, but more often, a doctor will order an MRI of one particular part of the body.

Evidence of iron accumulation on a brain MRI is often an important clue leading to diagnosis. A T2 sequence is the preferred type of MRI for NBIA diagnosis because it is highly sensitive to the detection of brain iron.

MRI findings for neuroferritinopathy include:

- Hypointensity (darkness) in the caudate, globus pallidus, putamen, substantia nigra, and red nuclei on T2 MRI

- The dark patches indicate iron accumulation

- Eventually leads to cystic changes and cavitation in the caudate and putamen which appear as patches of hyperintensity (brightness)

Diagnosis of neuroferritinopathy can be confirmed through genetic testing of the FTL gene to find a gene change. Genetic testing is done through sequence analysis, which is able to find the gene change in ~80% of cases.

Rarely, an individual with the signs and symptoms of neuroferritinopathy may not have a gene change identified. This can happen because the genetic testing is not perfect and has certain limitations. It does not mean the person does not have neuroferritinopathy; it may just mean we do not yet have the technology to find the hidden gene change. In these cases it becomes very important to have doctors experienced with neuroferritinopathy review the MRI and the person’s symptoms very carefully to be as sure as possible of the diagnosis.

MANAGEMENT

There is no standard treatment for neuroferritinopathy. Diagnosed individuals are managed by a team of medical professionals that recommends treatments based on current symptoms.

There is no standard treatment for neuroferritinopathy. Diagnosed individuals are managed by a team of medical professionals that recommends treatments based on current symptoms.

After diagnosis, individuals with neuroferritinopathy are recommended to get the following evaluations to determine the extent of their disease:

- Psychometric assessment

- Physiotherapy assessment

- Speech therapy assessment

- Dietary assessment

- Medical genetics consultation

The movement problems are difficult to manage but some individuals have shown a response to standard doses of the following medications:

- Levodopa

- Tetrabenazine

- Orphenadrine

- Benzhexol

- Sulpiride

- Diazepam

- Clonazepam

- Deanol

- Botulinum toxin (helpful for painful focal dystonia)

The symptoms of parkinsonism can be treated with the same medications used in Parkinson’s disease. Treatment with dopamine agonist drugs (like levodopa) must be started and monitored carefully. In the beginning, the dose is increased gradually until both the patient and doctor feel symptoms are under control. While taking dopaminergic drugs, individuals must be regularly monitored for adverse neuropsychiatric effects, psychiatric symptoms and worsening of parkinsonism. The benefits of the medication usually only last a few years and are eventually limited by the development of disabling dyskinesias (difficulty performing voluntary movements).

Even after a diagnosis has been made and the appropriate therapies have been decided, it is recommended to continue long-term surveillance to decrease the impact of neuroferritinopathy symptoms and increase quality of life.

Long-term surveillance for neuroferritinopathy can include:

- Regular assessment of nutrition and caloric intake

- Physiotherapy to maintain mobility and prevent contractures (permanent tightening of a muscle or joint).

PROGRESSION

Movement problems typically affect one or two limbs in the beginning, eventually progress to all the limbs within 5-10 years and can become more generalized within 20 years. Over time, mental decline and behavioral issues become significant problems for individuals with neuroferritinopathy.

The average lifespan varies for individuals with neuroferritinopathy, but due to improvements in medical care, more affected individuals are now living well into late adulthood.

Copyright © 2014 by NBIAcure.org. All rights reserved.